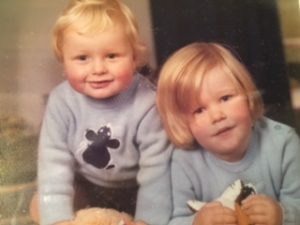

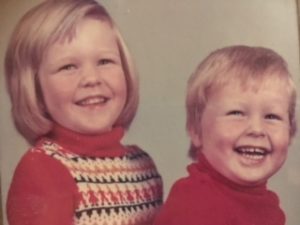

Andrew and I were complete opposites, particularly as children. I was the sociable, chatty one and bossed him around a lot; Drew was quiet, clever, a home bird. He loved his lego, playing cricket or building bonfires in the garden with Dad (autumn was his favourite time). I ate everything and he ate fishfingers and chips. I remember our grandpa offering him 50p to eat a slice of beef, but he couldn’t do it. I pranced around the lounge doing dance routines, whilst Drew sat on the sidelines, doing my “lighting” with an Ever Ready torch.

Andrew never sought the limelight, but that shy little boy grew up to become not just talented and successful (a straight A student, an accomplished athlete, an award-winning architectural lighting designer) but also kind, loyal, decent, generous, funny and in the end probably more sociable than me.

Andrew died in the summer of 2015, whilst on holiday with his young family in Pembrokeshire. He was 41. It happened the day after they’d arrived. He’d spent an idyllic day on the beach with his wife, in-laws and his two little girls (then aged just 1 and 4), had dinner in the holiday house, was in bed playing games on his i-pad and then… gone. The autopsy reported “natural causes” but we’ve been told it was almost certainly the result of an undiagnosed heart condition. Andrew had never smoked, drank modestly and apart from a stressful job was as fit and healthy as you could imagine.

I remember seeing the missed call from my sister-in-law very early the morning after he died and thinking it must have been one of my nieces playing on the phone. But then my husband rang (I was at my parents’ house) and I just knew before he spelt out the words. It was the most devastating feeling.

I definitely got lots of support from my friends and family after Drew died but it was also quite a lonely experience. Andrew was my only sibling, so whilst of course in my heart I will always have a brother, there was a sudden sense of being an only child. Certainly that’s what I am in practical terms. Telling my parents that Drew had died was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. Mum suffers from a degree of vascular dementia (after some partial strokes), which meant that she found absorbing the news even harder, and for a while I had to keep reminding her that it had happened.

I think as a sibling I’ve also felt as if my grief could never be as great as that of my sister-in-law or my parents. In a sense concentrating on them – my parents in particular as they are quite elderly and vulnerable – helped me cope, because it kept my own feelings at bay. I got through things by applying a sticking plaster – metaphorical, obviously – which kept the wound covered. I’d lift it up sometimes and then hurriedly replace it when I realised how raw it was. But the wound can only heal if you expose it, and whilst that hurts, in the long run it’s definitely better. Sometimes you won’t want to talk and share stuff, but you need to do it sometimes and it does feel better when you do.

At the moment I feel Andrew’s loss most when I look at the family he has left – when my mum cries and when I see his gorgeous family missing the husband and dad they loved so much. As time goes on I think I will miss the person I grew up with, the one who latterly was my team mate in parental care, the one other person who really understood the quirks of our little family – my irreplaceable brother.